Introduction

New England's textile mills played a huge role in the birth of American industry, marking the start of the country's transformation into an industrialized nation. In the 19th century, the introduction of water-powered textile mills along New England's rivers used the region's natural resources, which resulted in rapid economic growth. Key figures such as Samuel Slater and Francis Cabot Lowell brought new manufacturing techniques to the US, revolutionizing production methods and paving the way for the factory system that would define this era.

This site provides an in-depth exploration of New England's textile industry, from the initial development of these mills to the social and technological advancements they created. We will cover various aspects of the factory system, including its impact on workers and the surrounding community. A special section is dedicated to the Lowell Mill Girls, young women who made up a significant portion of the workforce and whose experiences reveal much about the labor conditions, social expectations, and the early labor rights movement.

The Early Years

The textile industry in New England began in the late 18th century, fueled by a combination

of ingenuity, resource availability, and growing demand. As the U.S. sought economic independence

following the American Revolution, entrepreneurs looked to textile manufacturing as a promising

industry that could help the young nation become less reliant on imported British goods. New England,

with its fast-flowing rivers, abundant natural resources, and ports for shipping, was the ideal location

for this new industry.

The industry's journey began with Samuel Slater, a British immigrant often called the "Father of

the American Industrial Revolution." In 1790, Slater established the first successful textile mill in Pawtucket,

Rhode Island, using his knowledge of British textile machinery to replicate their designs in the United States.

Slater's mill marked a turning point, and soon, other mills started springing up across New England, each eager to

capitaliize on this new way of producing textiles.

There was a lot of excitement around these new factories. Textile mills represented a break from traditional

methods of hand-weaving and spinning, introducing the concept of large-scale production that could meeet the growing needs

of the American population. Investors were eager to back this industry, and communities developed around these factories,

providing a steady workforce and supporting infrastructure. Towns like Lowell, Massachusetts, were built specifically to

house and employ workers for the mills, creating industrial communities that became models for other regions.

These early years were marked by rapid innovation and adaptation. The initial mills were powered by water, using the force of

rivers to drive large machines capable of processing cotton and wool at unprecedented speeds. The efficiency and productivity of

these mills soon transformed New England into an industrial hub, setting the stage for a more significant transformation in the

American economy and society.

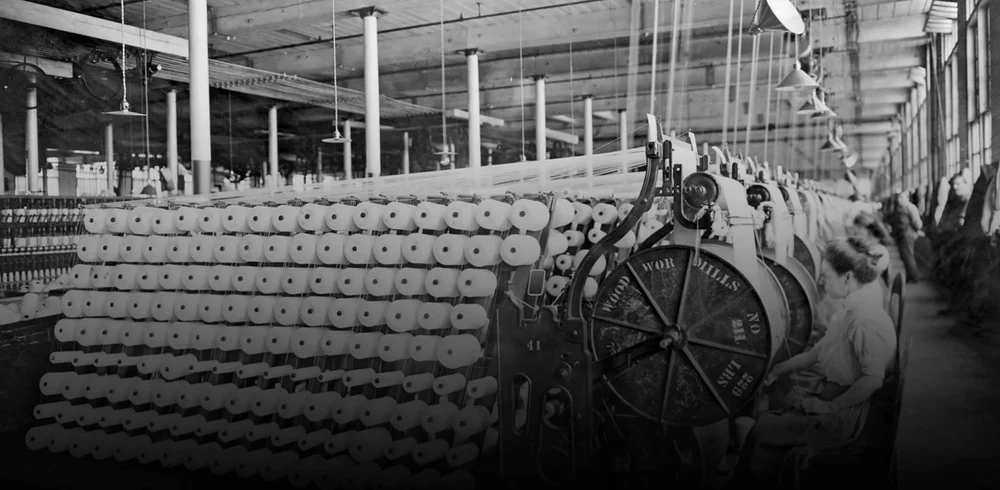

Textile Mills of New England

The New England Textile mills were the core around which the region's industrial growth would be set and consequently transformed

both its physical and social landscape. Throughout the late 18th and 19th centuries, mills sprouted along New England's rivers and

waterways to power machinery. Not simply structures themselves, the mills were complex systems of production that conveyed state-of-the-art

technology and new forms of labor organization. One of the biggest and best-known of these early mills was in Lowell, Massachusetts,

popularly known as the "Cradle of the American Industrial Revolution." Founded in 1820s, Lowell would become the largest and most

successful mill town in the United States. The city was well-planned, with large brick factory buildings, canals to transport goods in and

to run mill machinery, and boarding houses for its employees.

Each mill was an engineering marvel: early versions used water wheels, while more advanced versions used water-powered turbines for increased

productivity. Machines such as spinning jenny, power loom, and carding machines worked together in an automated process of changing raw cotton

into finished cloth. This process was much more effective than hand weaving and, therefore, enabled faster and cheaper production of textiles.

As these mills expanded, they had to hire many workers. Most New England mills hired mainly women and children because they were "cheap labor," meaning their

wages were lower than average. Suddenly, young women could go out and earn an independent income. Most of them were the so-called "Lowell Mill Girls" who migrated

from the countryside to the mills, attracted by the promises of regular pay, companionship, and the chance to be involved in this revolutionary

industry.

And yet, with the opportunities, life in the mills was not easy: workers had to work long hours, often from morning well into the night, amidst noise,

a crowd, and cotton dust with machinery. The work was hard and dangerous, with almsot no protection against accidents. Yet the mill town became the

axis of social life in the worker communities residing in towns and boarding houses outside the factories. With increased mills, economic assets increased

hand in hand with social challenges. There was labor turmoil, where workers fought for shorter hours and improved working conditions and wages.

Mills became the cradle of early movements when several workers organized themselves into strikes and petitions protesting for their rights.

Consequently, New England's textile mills did more than turn out products; they gave rise to America's industrial character. These mills furthered economic

growth, new technologies, and an evolution in social structures. Even today, remannts of such mills testify to the ingenuity and grit of the people who manned them

and the region that fostered their growth.

The Lowell Mill Girls

The Lowell Mill Girls were a workforce of young women who became vital to the success of the textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts, during the early stages of the Industrial Revolution in America. They represented a vital shift in society as women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers, seeking financial independence and personal growth. Their experiences revealed the complexities of industrial life, the evolution of labor activism, and the broader cultural changes of the 19th century.

Who were they?

The Lowell Mill Girls were mostly daughters of New England farmers, often aged between 15 and 30. Most came from small towns and rural communities where their families relied on subsistence farming. Economic challenges, such as declining farm profits and limited opportunities for women, prompted many families to send their daughters to work in the mills. Unlike the immigrant laborers who later dominated the factory workforce, the Mill Girls were largely native-born and Protestant. They were viewed as honest, passionate young women who supported New England's cultural values. Many of these women saw millwork as a temporary phase, planning to save money for education and financial support for their families before marrying and returning to traditional domestic roles. This distinct demographic gave the Mill Girls a unique identity within the industrial workforce. They were seen not merely as laborers but as pioneers of women's economic participation, blending traditional values with the new realities of industrialization.Recruitment, Demographics, and Motivations for Working

Recruitment efforts by mill owners played a critical role in shaping the workforce. Advertisements and word-of-mouth campaigns emphasized the benefits of working in the mills. Mill agents targeted young women by promising a safe, supervised environment and the opportunity to earn wages, which was a rare opportunity for women in the 19th century. The boarding houses, strict oversight by other ladies, and proximity to churches were key selling points. These measures reassured parents who might otherwise hesitate to send their daughters to an industrial town, preservering the image of Lowell as a moral and orderly community. For the Mill Girls, motivations varied. Many sought independence and a break from the repetitiveness of rural life, while others worked out of financial necessity. The ability to send money home to support their families or save for their futures made millwork an attractive, albeit demanding option. The prospect of living and working among peers in a packed milltown also appealed to those who were looking for new experiences.Life in the Mills: Boarding Houses, Workdays, and Social Lives

Life for the Lowell Mill Girls were characterized by both friendship and hardship. Upon arrival, workers typically lived in company-owned boarding houses. These houses were managed by women who enforced strict rules, such as curfews, to ensure moral conduct. Each house accommodated 20 to 40 women, with shared bedrooms and communal meals. While these arrangements fostered a sense of community, they also meant little privacy or personal space.The workdays were long and physically burdening. A typical day began at 5:00 AM and ended around 7:00 PM, with breaks for meals. The mills were filled with the deafening roar of machinery, and conditions were often hazardous. Cotton dust filled the air, leading to respiratory issues, while the risk of injury from the fast-moving machines was always present. Despite these challenges, the Mill Girls took pride in their work seeing it as a contribution to the growing economy.

In their free time, the women developed a vibrant social and intellectual life. They attended lectures, participated in church activities, and formed close friendships within the boarding houses. Many were avid readers and writers, discussing literature, philosophy, and current events. This intellectual engagement set them apart from other industrial workers of the time.

Labor Activism: Strikes of 1834 and 1836

The Lowell Mill Girls were among the first industrial workers in the Untied States to organize and protest against poor working conditions. These early efforts were groundbreaking and symbolic of the growing tension between labor and capital in the early industrial era.In 1834, when mill owners announced a wage cut, the Mill Girls organized a "turnout" (an early term for strike). They marched through the streets of Lowell, protesting the reduction in their already mediocre pay. Although the strike was unsucessful, it demonstrated the workers' willingness to challenge their employers' authority.

Two years later, in 1836, the Mill Girls staged another strike in response to an increase in rent at the boarding house. Over 1,500 workers participated, arguing that the rent hike reduced their earnings. While this strike also failed to achieve its immediate objectives, it marked a critical moment in the history of labor activism. These protests highlighted the Mill Girls' awareness of their rights and determination to fight for fair treatment.

Contributions to Literature: The Lowell Offering

One of the Mill Girls' most lasting legacies is their literary contributions to The Lowell Offering. This magazine, first published in 1840, was written entirely by the Mill Girls and showcased their essays, poems, and stories. It allowed them to share their experiences, thoughts, and creativity with a broader audience.Through The Lowell Offering, the Mill Girls challenged stereotypes about female factory workers, presenting themselves as thoughtful, fluent people with a sharp interest in literature and intellectual pursuits. Their writings often reflected the differences of their lives: the pride in their work contrasted with the struggles they faced in the mills.

The magazine gained national attention, with readers admiring the clarity and insight of the contributors. Today, The Lowell Offering is considered a valuable historical resource, offering a rare glimpse into the lives of working women during the Industrial Revolution.

Working Conditions & Labor Movements

The working conditions in New England's textile mills were known for its harsh conditions. Long hours, hazardous environments, and minimal worker protections illustrated the daily life of mill operators, particularly the young women known as the Lowell Mill Girls.

Laborers typically worked 12-14 hour shifts, six days a week, in environments filled with deafening machinery and air saturated with cotton dust, leading to respiratory and other health issues. Accidents were expected due to to the fast-moving, unguarded machines, and the

absence of safety regulations left workers vulnerable to injuries and even fatalities.

The mills' reliance on female labor was a social and economic strategy. Mill owners employed young women because they could pay them less than male workers, often between $2 and $4 per week. The boarding houses where they lived were highly disciplined, with curfews and strict

codes of conduct enforced by matrons. Though these living conditions provided a degree of security, they also limited personal freedom and independence.

The harsh conditions and low wages eventually started organized resistance among mill workers. In 1834, the Lowell Mill Girls led one of the first strikes in U.S. history after a proposed wage cut. Although the strike failed, it set an example for future labor activism.

Two years later, in 1836, another strike erupted in response to increased boarding house rents, involving over 1,500 workers. This time, although the strike failed to acheive its immediate goals, it marked the growing awareness of workers' rights and the need for collective action.

The strike laid the groundwork for more organized labor movements in the late 19th century. These movements sought to address broader issues such as child labor, workplace safety, and fair wages, ultimately leading to labor unions and state regulations like the Factory Acts, which sought

to improve conditions for industrial workers.

Despite their challenges, the Lowell Mill Girls played a vital role in shaping early labor activism in the United States. Their efforts helped to challenge the notion of passive female labor and dedmonstrated the potential for organized resistance to industrial exploitation.

Technology & Innovation in the Mills

The New England textile mills, particularly those in Lowell, Massachusetts, were not just centers of production; they were hubs of technological advancement that rehsaped industry and society in 19th-century America. These innovations, driven by the need for efficiency and profitability,

transformed the mills into highly productive companies and laid the foundation for future industrial developments.

Harnessing Water Power: The Engine of Industrial Growth

The Lowell mills' sucess depended on their ability to use water power efficiently. With its fast currents and consistent flow, the Merrimack River provided an ideal energy source for large-scale manufacturing. However, using this natural resource required significant engineering feats. To maximize the river's potential, the Proprietors of Locks and Canals constructed an intricate canal system that redirected water to multiple mill complexes. These canals, meticulously designed and maintained, fed water into turbines and waterwheels, which converted the kinetic energy of flowing water into mechanical power to operate the mills' machinery. Unlike traditional mills that relied on single waterwheels, Lowell's mills used multiple turbines in tandem, allowing for greater energy output and operational flexibility. This innovation ensured a continuous power supply, even during periods of low water flow or drought, making the mills far more reliable than earlier rural operations. The success of this system made Lowell a model for other industrial cities, inspiring similar developments in places like Lawrence, Massachusetts, and Manchester, New Hampshire.Beyond powering machinery, the water system shaped Lowell's physical and economic landscape. The city was carefully planned around its canals, with mill buildings, boardinghouses, and transportation infrastructure designed to maximize efficiency. This integration of natural resources and urban planning represented a new approach to industrial development in America, prioritizing both productivity and sustainability.

The Lowell System: Vertical Integration and Industrial Efficiency

The "Lowell System," also known as the Waltham-Lowell System, was a groundbreaking industrial organization model that set the mills apart from earlier manufacturing practices. This system centralized all aspects of textile production within a single facility, streamlining the process from raw cotton to finished cloth.At a time when many manufacturers relied on a "putting-out system," in which independent artisans or small workshops completed various stages of production, the Lowell mills consolidated everything under one roof. This vertical integration reduced transportation costs, minimized delays, and allowed for better quality control. By managing the entire production process internally, the mills could respond more quickly to fluctuations in market demand, adjust output levels, and maintain consistent standards across their products.

The Lowell System also emphasized a highly regimented work environment. Each task in the production process was carefully timed and monitored, ensuring a steady flow of materials from one stage to the next. This assembly-line manufacturing approach increased productivity and reduced the need for skilled labor, as workers were trained to perform specific tasks rather than mastering the entire production process. This efficiency translated into lower production costs, making Lowell's textiles highly competitive in domestic and international markets.

Innovative Textile Machinery: Automating Production

Technological innovation within the Lowell mills extended beyond water power to include groundbreaking advancements in textile machinery. Among the most significant was the adoption and improvement of the power loom, a device that automated the weaving process. Initially developed in England, the power loom allowed mills to produce fabric faster and more precisely than traditional hand looms.In addition to the power loom, the mills utilized spinning frames to automate the transformation of raw cotton into thread. These machines, often operated by a single worker, could handle multiple spindles simultaneously, significantly increasing yarn output. This mechanization boosted productivity and reduced the physical labor required, making it possible for a predominantly female workforce to operate the machinery efficiently.

Another critical innovation was the introduction of the Jacquard loom. This device, controlled by a series of punched cards, enabled the automated production of complex patterns in woven fabrics. Before this innovation, creating intricate designs required highly skilled artisans and considerable manual labor. The Jacquard loom democratized patterned textiles, allowing the mills to produce a wider variety of fabrics and cater to diverse consumer preferences.

These technological advancements were continuously refined and improved upon, with mill owners investing heavily in research and development to maintain their competitive edge. Over time, the machinery in the Lowell mills became more sophisticated, incorporating features like automatic shut-offs, tension control mechanisms, and quality inspection systems.

Labor Organization and Productivity: Managing the Workforce

The success of the Lowell mills were not solely due to technological innovation; it also depended on the effective organization of labor. The workforce, composed primarily of young women from rural New England, were vital to the Lowell System. These "mill girls" were recruited with promises of steady wages, educational opportunities, and a chance to experience life in a growing industrial city.To maximize productivity, the mills implemented a highly structured work environment. Workers were organized into shifts, typically 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week. Timekeeping systems, such as factory bells and clocks, regulated the workday, ensuring that production schedules were adhered to strictly. This level of discipline and organization was critical to maintaining the steady flow of materials and output required by the mills. The mills also provided company-owned boardinghouses for their workers. These residences near the factories offered affordable housing, meals, and a sense of community. While the boardinghouses were often crowded and tightly regulated, they provided stability and support that was uncommon for industrial workers at the time. Many mill girls participated in cultural and educational activities, such as attending lectures, joining reading clubs, and contributing to publications like The Lowell Offering, a literary magazine written by and for the mill workers.

Legacy and Impact: Shaping the Future of American Industry

The innovations developed in the Lowell mills had a lasting impact on American industry and society. By demonstrating the feasibility of large-scale, mechanized production, the mills helped to shift the United States from an agrarian economy to an industrial powerhouse. The success of the Lowell model inspired the creation of other industrial cities and influenced the development of industries beyond textiles, including steel, railroads, and eventually automobiles.The efficiency, vertical integration, and labor management principles established in Lowell became central to the American industrial ethos. These practices contributed to the economic growth of the 19th and 20th centuries and laid the groundwork for modern manufacturing systems. The legacy of the Lowell mills can still be seen today in the structure and organization of contemporary industries, making them a pivotal chapter in the story of American innovation.

Social & Economic Impacts

New England's textile mills were more than just centers of industrial production; they were catalysts for significant social and economic transformations in the United States. The mills left a lasting legacy on American society by reshaping labor practices, fostering urban growth, and influencing economic policies.

Economic Growth and Urbanization

The establishment of textile mills in New England, particularly in cities like Lowell, produced rapid economic growth. These mills created thousands of jobs, attracting workers from rural areas and fostering the development of industrial towns. What began as small villages quickly transformed into bustling urban centers, complete with factories, housing, and infrastructure.Once a modest agricultural community, Lowell became a model industrial city and a hub of commerce. The influx of workers led to the development of markets, schools, and transportation networks, creating a self-sustaining urban economy. This pattern of industrialization and urbanization was replicated in other regions, contributing to the broader shift from a predominantly agrarian economy to an industrialized nation. The mills also stimulated the growth of related industries, such as transportation and trade. Railroads and canals were built to transport raw cotton to the mills and finished textiles to markets, linking New England to the southern United States and international trade networks. This interconnectedness facilitated the rise of a national economy, with textile production playing a central role.

Shifts in Labor Dynamics

The mills brought about profound changes in labor dynamics, particularly in women's employment. The majority of the workforce in the Lowell mills consisted of young, unmarried women from rural New England, known as the "mill girls." This marked a departure from traditional labor patterns, where women typically worked at home or in small-scale cottage industries.For many of these women, millwork offered a rare financial independence and social mobility opportunity. Meanwhile, modest wages were often higher than women could earn through domestic work or farming. Mill girls used their earnings to support their families, save for dowries, or fund education, challenging traditional gender roles and expectations. However, the mills also introduced new challenges, such as long working hours, strict supervision, and the physical demands of factory labor. Over time, the exploitative nature of millwork led to growing discontent among workers, culminating in strikes and labor protests. The strikes of 1834 and 1836, led by mill girls, were some of the earliest examples of organized labor activism in the United States, setting the stage for future labor movements.

Cultural and Social Changes

The mills not only transformed the economic landscape but also significantly impacted social and cultural life. The close-knit communities that developed around the mills fostered a unique social environment where workers could form friendships, participate in cultural activities, and engage in intellectual pursuits.The publication of The Lowell Offering, a literary magazine written by and for the mill girls, exemplified this cultural engagement. Through essays, poetry, and stories, the magazine provided a platform for mill workers to express their thoughts, share their experiences, and reflect on issues such as labor conditions, education, and women's rights. This intellectual and cultural output challenged prevailing stereotypes of factory workers as uneducated and unrefined, highlighting their capacity for creativity and critical thought.

The mills also contributed to the broader discourse on social reform. Mill workers' experiences, particularly their struggles for fair wages and better working conditions, drew the attention of reformers and activists. Prominent figures, such as labor advocates and women's rights activists, used the plight of mill workers to argue for broader social and economic reforms, including improved labor laws and expanded educational opportunities for women.

Economic Disparities and Class Tensions

While the mills brought economic prosperity to some, they also highlighted and, in some cases, exacerbated economic disparities and class tensions. Mill owners and investors, often from affluent backgrounds, reaped significant profits from the labor of factory workers, leading to stark differences in wealth and living conditions.Despite their contributions to industrial growth, factory workers often lived in overcrowded boardinghouses and faced harsh working conditions. The long hours, low wages, and lack of job security created a precarious existence for many workers, fueling resentment and class tension. This divide between labor and capital became a defining feature of industrial society, prompting debates over workers' rights, economic justice, and the role of government in regulating industry.

Legacy and Long-Term Impact

The social and economic impacts of the New England textile mills extended far beyond their immediate operations. They played a crucial role in shaping the trajectory of American industrialization, setting precedents for labor organization, urban planning, and economic development.The mills also left a lasting legacy in the realm of social reform. Mill workers' experiences, particularly their efforts to advocate for better working conditions and greater social recognition, contributed to the emergence of labor unions, women's rights movements, and educational reforms. Today, the story of the New England textile mills serves as a reminder of the complex interplay between technology, labor, and society in shaping modern America.

References

Crafts, N. F. R., & Wolf, N. (2013). The location of the UK cotton textiles industry in 1838: A quantitative analysis. CORE. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from

https://core.ac.uk/download/19553696.pdf

Fields, M. D. (2019). Women in American labour movement: Overcoming exclusion and sex-based discrimination. International Journal of Public and Private Perspectives on Healthcare, Culture, and the Environment (IJPPPHCE), 3(2), 59–66. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from

https://doi.org/10.4018/IJPPPHCE.2019070104

Freeman, E. (1994). ‘What factory girls had power to do’: The techno-logic of working-class feminine publicity in *The Lowell Offering*. Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory, 50(2), 109–128. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from

https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/arq.1994.0000

Frommer, W. H., & Tetrault, E. B. (1955). New England problem town: Public relations factors in rehabilitating a community which has lost its major industry. Open BU. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from

https://open.bu.edu/bitstream/2144/6476/1/Frommer_Walter_1955_web.pdf

Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. (n.d.). Lowell mill girls and the factory system, 1840. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from

https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/lowell-mill-girls-and-factory-system-1840

Greenlees, J. (2013). ‘For the convenience and comfort of the persons employed by them’: The Lowell Corporation Hospital, 1839-1930. CORE. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from

https://core.ac.uk/download/293874935.pdf

McNamara, R. J. (2021, May 23). The Lowell mill girls in the 19th century. ThoughtCo. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from

https://www.thoughtco.com/lowell-mill-girls-1773968

Merish, L. (2012). Factory labor and literary aesthetics: The ‘Lowell Mill Girl,’ popular fiction, and the proletarian grotesque. Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory, 68(4), 1–34. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from

https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/arq.2012.0022

National Park Service. (n.d.). Building America’s Industrial Revolution: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from

https://www.nps.gov/articles/building-america-s-industrial-revolution-the-boott-cotton-mills-of-lowell-massachusetts-teaching-with-historic-places.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.). Lowell handbook: Seeds of industry. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from

https://home.nps.gov/articles/lowell-handbook-seeds-of-industry.htm

Perritt, H. H., Jr. (2020). Job training mythologies: Stitching up labor markets. CORE. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from

https://core.ac.uk/download/322975252.pdf

Putzi, J. (2016). Poets of the loom, spinners of verse: Working-class women’s poetry and The Lowell Offering. In J. Putzi & A. Socarides (Eds.), A history of nineteenth-century American women’s poetry (pp. 155–169). Cambridge University Press.

Smith, R., & O'Connell, P. (1997). Workers on the line: Teaching industrial history at the Tsongas Industrial History Center and Lowell National Historical Park. OAH Magazine of History, 11(2), 22–26. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from

https://doi.org/10.1093/maghis/11.2.22

Sheldon, C. (2021). The motivation to volunteer: Understanding volunteer motivation at United States industrial heritage museums and organizations. CORE. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from

https://core.ac.uk/download/428349859.pdf

Tyson, T. N. (1992). Nature and environment of cost management among early nineteenth century U.S. textile manufacturers. CORE. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from

https://core.ac.uk/download/288065882.pdf

Trajtenberg, M., & Rosenberg, N. (2024). A general purpose technology at work: The Corliss steam engine in the late 19th century US. CORE. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6586387.pdf

Wright, C. (n.d.). Lowell mills and the industrial revolution. Teach US History. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from

https://www.teachushistory.org/textiles/